Combining already transcribed comments and adding the comments from earlier in 2019, here is the word cloud from all 564 comments made in the visitor book during 2019. Every one of the comments was positive!

Combining already transcribed comments and adding the comments from earlier in 2019, here is the word cloud from all 564 comments made in the visitor book during 2019. Every one of the comments was positive!

Exhibition: John Muir, Earth-Planet, Universe

Preview, Q&A and Discussion

Wednesday 26th February 2020 at 7:30pm

Community Room, Dunbar Town House

This public event is a preview of the Friends’ forthcoming 2020 exhibition followed by a Q&A and discussion on the theme of What If?

See John Muir, Earth-Planet, Universe for further details.

In 2020 Friends of John Muir’s Birthplace are working together with other groups in Dunbar to focus on Muir’s role as an environmental activist and successful campaigner and his relevance for our situation today. In an emergency, we have to behave differently and act swiftly. How are we doing that? From April to October the exhibition at the Birthplace will support the review and expansion of the John Muir’s Legacy section of the permanent exhibition. The aim is to:

In 2020 Friends of John Muir’s Birthplace are working together with other groups in Dunbar to focus on Muir’s role as an environmental activist and successful campaigner and his relevance for our situation today. In an emergency, we have to behave differently and act swiftly. How are we doing that? From April to October the exhibition at the Birthplace will support the review and expansion of the John Muir’s Legacy section of the permanent exhibition. The aim is to:

With the Exhibition as a starting point, to focus on:

Wednesday 26th February 2020 at 6:45pm for 7:00pm

Council Chambers, Dunbar Town House, High Street, Dunbar

Agenda

(i) Report of year’s activities

(ii) Filling any vacancies on Council [1]

(iii) Other competent business

Non-members will be warmly welcomed and after the AGM business – at 7:30pm in the Community Room – there will be a short preview of the Friends’ forthcoming 2020 exhibition (see John Muir, Earth-Planet, Universe) followed by a Q&A and discussion on the theme of What If?

As Convener of Friends of John Muir’s Birthplace (FoJMB) I’ve often found myself using the phrase ‘Inspired by Muir’. Personally, I’ve also found inspiration from Muir’s life and work and actively promote and support initiatives that bring Muir and his legacy to the attention of a wider public.

In 2019 FoJMB celebrated its 25th anniversary. In July 1994 Dunbar’s John Muir Association – as FoJMB was then known – was established. Much has been achieved by the charity since then but what will the next 25 years bring? Continuing to support the work of the Birthplace and actively collaborating with the other partners in the John Muir Birthplace Trust is a given. If anyone who is reading this would like to contribute their time and expertise to furthering the aims and objectives of FoJMB please consider standing for Council. I also encourage all members to ‘recruit’ others to our cause if at all possible.

Our 2020 exhibition departs somewhat from the pattern of concentrating on the life and legacy of John Muir. This exhibition will, of course, acknowledge Muir’s advocacy in protecting nature. However, it also addresses the issues that now impact on every living thing that relies on planet Earth for survival!

Duncan Smeed, FoJMB Convener

[1] Nominations for Council accompanied with the nominee’s agreement in writing and items for consideration under other competent business should be lodged with the Secretary, c/o John Muir’s Birthplace Museum, 126 High Street, Dunbar, EH42 1JJ by Friday 21st February 2020.

After the business of the Extraordinary General Meeting on 14th August 2019 I gave a short presentation about the achievements and milestones of DJMA/FoJMB over the past 25 years (see link below). This was followed by a short discussion – to be continued at a later date – about future plans and aspirations for our Charity.

Duncan Smeed, FoJMB Convener

Twelve members of Friends of John Muir’s Birthplace (FoJMB) attended the Extraordinary General Meeting on 14th August 2019. Nine members presented their apologies and, of these, six had given written permission to have the Chair, or a named attendee, to cast a proxy vote on their behalf.

Prior to the vote I explained that should the motion be carried it would mean that paid membership would cease and that anyone wishing to become a member of FoJMB would, in effect, simply let the charity know their contact details and give their permission to be contacted with news about the activities of the charity. Consequently, the arrangement whereby a 10% discount would apply to sales from the Birthplace ‘shop’ for members would no longer apply.

The motion to waive membership dues was proposed by Liz McLean and seconded by Ross Combe. The motion was carried unanimously.

This means that members no longer need to pay membership dues and since October is the month where the majority of dues are renewed there is ample time to cancel standing orders before that payment is taken. Of course, should members wish to continue such payments as donations to the charity we would be very grateful for that income stream.

A specific reason for opening up membership to anyone that gives their permission to be contacted with news about the activities of the charity is that FoJMB can, hopefully, reverse the trend of members ‘leaving’ if they don’t renew their paid membership and, therefore, build up the numbers of supporters (Friends) and to then approach them when a specific project – such as an exhibition – needs donations to help fund it.

Given the outcome of the EGM there will now be a renewed effort to engage with potential supporters and to introduce some convenient methods for them to ‘sign up’. In the first instance this could be as simple as emailing info@muirbirthplacefriends.org.uk with contact details and a confirmation that it is OK to hold these details on record for the legitimate purposes of the charity. In a subsequent reply to this request to join the following text will confirm our compliance with GDPR:

In compliance with General Data Protection Regulation (EU 2016/679), the information provided will be used solely for the legitimate purposes of the Charity. Any personal details gathered will be used solely by FoJMB and will not be provided to any third parties outwith the Charity.

After the business of the EGM, I gave a short presentation about the achievements and milestones of DJMA/FoJMB over the past 25 years. This was followed by a short discussion – to be continued at a later date – about future plans and aspirations for our Charity.

Duncan Smeed, FoJMB Convener

As mentioned in the ‘Stop Press: Robert Burcher’s Visit to Dunbar’ article in the Spring 2019 Newsletter, Robert – a Muir enthusiast from Meaford, Canada – has very kindly offered to give an illustrated talk about the “Canadian John Muir” when he visits Dunbar. This is now scheduled to take place in the John Muir Birthplace on Friday, 6th September at 3:30pm. There may even be tea and biscuits on the programme too!

This event is open to everyone – not just members of Friends of John Muir’s Birthplace – but to help plan for numbers please RSVP. If the numbers attending are likely to exceed the capacity of the temporary exhibition space in JMB we will hold the event in the Council Chamber of Dunbar Town House.

Robert has provided a short bio about himself and some more background about his research into the Muir and Meaford connection.

It was disbelief when I saw the abandoned historic plaque in the Epping Lookout that stated that John Muir had lived in my valley – here in Ontario Canada – during the 1800’s. I never knew that! But with some sleuthing in museums and old textbooks I did find that it was a totally true but just an unknown fact to most people. Also too I discovered that most people in Canada had no idea who John Muir was. With the Civil War raging in the south, the Scottish born young man of 26 was sent north from the family farm in Wisconsin to live in Meaford and work at a sawmill for the two years from 1864 to 1866. Apparently he was totally at home with the Scottish Trout Family and formed lasting friendships during his time in the Canadian wilderness. Not only was he becoming hugely aware of the destruction of the forests at the time but he was also an incredible inventor and managed to double the production of the mill in one year. But in the winter of 1866 during a fierce winter storm the mill burned down with the whole year’s production of rake and shovel handles that had been stored in the attic. The Civil War was over and Muir returned penniless to the USA to work in Indiana.

In the summer of 1997 several of Muir’s letters sent to the Trout Family from Indiana were donated to the local museum. They didn’t know in fact who John Muir was! Because of my work in getting the plaque restored the letters came to my attention. I was able to by that time give a sketchy outline of the life of Muir and his time in Canada. The museum created an organization that eventually became The Canadian Friends of John Muir. Local naturalists and environmentalists got on board and it became a cause célèbre. In the summer of 1998 a major event was held to promote the John Muir “Discovery”. As part of the celebration two experts on Muir came from Western Canada to be the “talking heads” of the day.

The event started with a morning hike into Trout Hollow where the remnants of the dam still existed and what appeared to be the foundation of the mill. Connie Simmons (one of the experts) who was doing her PhD on Muir decided that she wanted to find the actual cabin site where Muir would have lived at the time. As an avocational archaeologist and also a Muir devotee I volunteered to help. Using one of the letters that Muir had sent to Meaford, Connie was able to read about the night the mill burned down “that from the cabin they could see the flames reflected across the mill pond”. Using that clue we worked our way upstream and when we got to what seemed to be an appropriate location I happened to notice a pottery shard – blue and white English pottery style in the debris from a groundhog hole. It seemed to be of the right vintage so we felt satisfied that we might have actually found the cabin site. Later in the day at the formal presentation the leader of the group announced that in fact a pottery shard had been found that very morning and that we might have found the long lost cabin site. What we didn’t know was that the Head of Archaeology from the Royal Ontario Museum was in the audience and he came forward and agreed that we did have an artifact. The next day we took him back to the site and he did find a treasure trove of ancient household artifacts such as spoons, bricks, more pottery shards and square headed nails.

The land owner who has family roots in the area going back to the 1800’s knew who Muir was and in fact carried a quote from Muir in his wallet. He was so impressed with what we had found that he sponsored an archaeological dig for the summer of 1999.

With a hired professional team and multiple volunteers we spent two weeks working the site; both the mill location and the cabin site. After finding the household artifacts one of the members of the group casting around a little further in the woods found what appeared to be chimney mortar. This eventually was proven to be the fireplace. Using a sketch that Muir had done during his time we were able to estimate the size of the cabin and sure enough found evidence of the log foundation for the cabin.

This was all exposed during a second annual hike sponsored by the Canadian Friends. But during the time of the dig many archaeologists showed up from around the province to give their input to the site. Over the 131 years river erosion had eaten away half of the earthen dam and whatever roads entered the site. There were many conflicting ideas on how the mill would have worked (undershot / overshot / in the flow etc.) Also where would the road accesses have been? What has really happened with the erosion and undergrowth during all these years?

This was a satisfying time for all; many artifacts, lots of camaraderie and a great amount of learning about Muir. In fact some of the thinkers in the group started to formulate opinions that Muir’s fundamental values and a sense of the need to save wilderness areas actually started here in this valley outside of Meaford Ontario.

To cap it all off after all was said and done, during the lead up to the Millienium change and all the hooferall about Y2K, the local Township was installing a generator to run their communication system on New Year’s eve when the world was supposed to grind to a halt. During the process the builders set their Works Department building on fire and it burnt to the ground – the biggest disaster caused by Y2K in our neighbourhood! In the ensuing redistribution of staff to reclaimed storerooms as temporary offices a map dating to 1858 of Trout Hollow was found. There was our answer, in all of its perfection, the layout of the site as Muir would have lived it. Almost exactly as we had figured out through the years of research and the weeks of digging. Now if all archaeology could have an ending like that! Hey kids just flip to the back of your textbook and double check your answers!

As of today you can see the artifacts and display at the Meaford Museum and take a hike into Trout Hollow starting from a park on the river in Meaford called Beautiful Joe Park. A wonderful valley and hollow that is now nicely overgrown with just some ruins of later industrial activity still lurking in the woods.

Robert Burcher

I am a retired newspaper photographer who has had an interest in John Muir for decades. I live close to Meaford Ontario Canada where Muir spent the years from 1864 to 1866. During that time period the Civil War in the USA was raging. During the 1990’s I was a member of a group called the Canadian Friends of John Muir who worked to promote the fact that in fact Muir had lived and worked in this early pioneer village.

More recently I have spent the last three years doing some sleuthing to figure out where Muir was in the summer of 1864; what he called “My Summer of Glorious Freedom”. This was the lost summer that there was no record of where he travelled. He had left Wisconsin USA in March and arrived in Meaford in October. Through some new information released in 2008 that Muir was a dedicated botanist who collected plants everywhere he went. I was able to follow his trail of plant specimens from the summer of 1864 as he sauntered around our province.

Robert Burcher

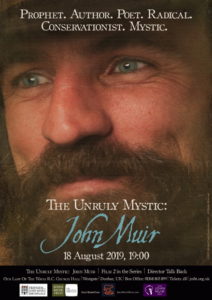

7pm, Sunday, August 18th

Our Lady of the Waves R.C. Church Hall, Westgate, Dunbar

Tickets*, £8

Friends of John Muir’s Birthplace is proud to host the Dunbar premiere of a new feature documentary on John Muir. Independent filmmaker Michael M. Conti will attend the screening of his film for an audience Q&A about the man often hailed as the founder of the world’s first national park system.

Friends of John Muir’s Birthplace is proud to host the Dunbar premiere of a new feature documentary on John Muir. Independent filmmaker Michael M. Conti will attend the screening of his film for an audience Q&A about the man often hailed as the founder of the world’s first national park system.

This beautifully photographed film explores the remarkable life and influential works of a patron saint of environmental activism. Against a backdrop of some of North America’s most exquisite scenery, the documentary considers the connection between nature and spirituality, using the life and wisdom of John Muir – ecological preservationist and founder of Yosemite National Park – to explore how being outside in nature affects the lives of everyday people right now.

Michael is sauntering along the John Muir Way in the week leading up to the screening in Dunbar and he will be documenting this experience via social media – www.facebook.com/johnmuirmovie/.

* Tickets are available at John Muir’s Birthplace during its normal hours of opening or Our Lady of The Waves R.C. Church hall just prior to the screening.